The impact of a brain injury affects not only the patient themselves, but also their families and society at large. Over the last 12 months, we have seen increasing number of headlines around the impact of early on-set dementia from sports-related traumatic brain injury.

Hippocrates dubbed it commotio cerebri or ‘commotion of the brain’. Today, the brain damage caused by head injuries and repeated concussions is called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) and it is recognised that it afflicts players and athletes of many other sports, including rugby, football and American football to name a few.

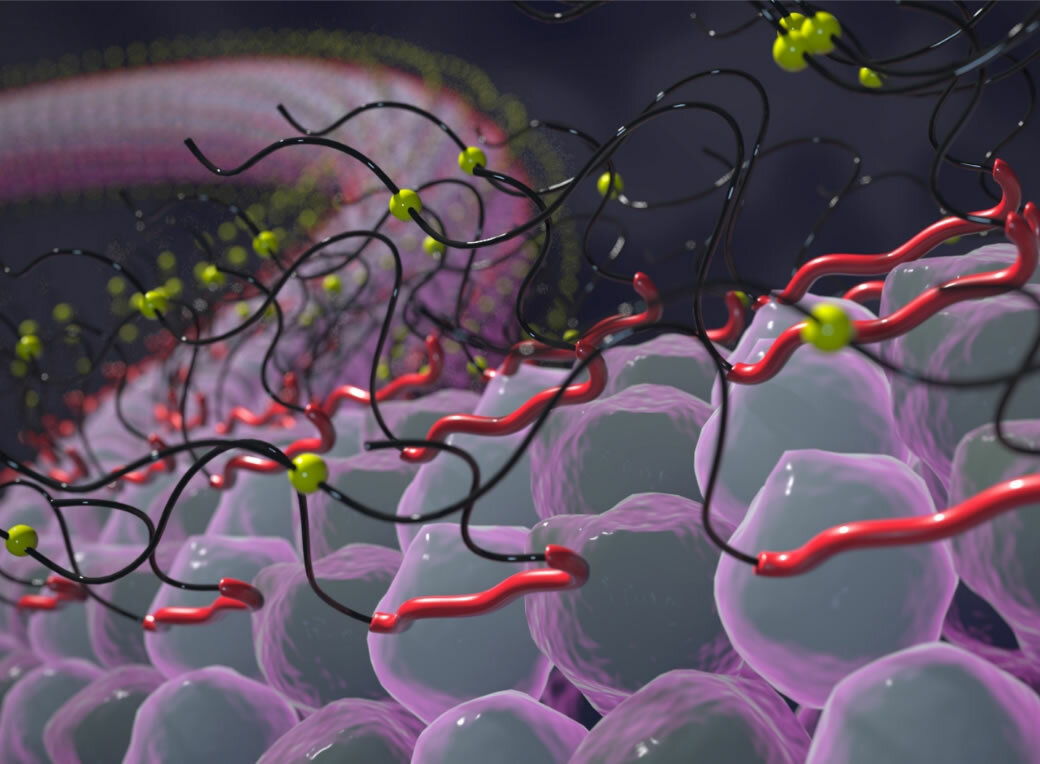

Paper after scientific paper, all rigorously researched and peer-reviewed, has established the connection between traumatic brain injuries and tau pathology. CTE shares key features with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, such as atrophy and tangles of tau protein in the brain that disrupt communication between brain cells.

With the connection made, many of those affected are now taking action. A group of 150 current and former rugby players, both male and female, are part of a group legal action against the sport’s governing bodies because they have been diagnosed with traumatic brain injury (TBI), early onset dementia and CTE.

The claimants are looking to some compelling precedents. A decade ago, The National Football League (NFL), the governing body for American football in the US, came to a billion-dollar settlement with more than 5,000 former players, after conceding that head trauma could have serious lasting consequences.

The issue has become so serious that the House of Commons’ Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee is conducting an inquiry – Concussion in Sport – into the links between sport and long-term brain injury.

However, most of the focus so far has been on mitigating risks in future. An international panel of experts called the Concussion in Sport Group (CISG) meets every four years to review the latest research and set protocols on best practice for handling head injuries such as rugby’s Head Injury Assessments (HIA). Elsewhere, moves to limit the amount of physical contact in training sessions (which account for as much as 90% of collisions experienced by professional players) and to ban tackling for under-18 players are all positive moves.

But risk reduction comes too late for the thousands of sportspeople who have already suffered head injuries and concussions and who are living in fear of developing the tell-tale symptoms of dementia. For all the earnest talk about reducing risk, there has been little said about actual treatment for this condition. There has been no mention of therapeutic research or clinical trials that could find potential solutions and offer peace of mind for those affected now, nor for the generations likely to be affected in the future.

However, greater understanding of tau pathology, the common link between sports-related early-onset dementia and other related diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Fronto-temporal Dementia could offer a way forward. Early clinical trial data suggests that tau aggregation inhibitors have potential to clear these tangled, or misfolded, proteins in order to slow clinical decline and reduce the damage to synaptic transmission and brain function.

Currently there are no disease-modifying therapies for former sportspeople suffering from the memory loss, cognitive impairment, confusion, depression, and behavioural changes that may accompany the early-onset dementia stemming from CTE.

Head injury in sport is not going to go away. But the powerful combination of committed governing bodies and scientific research could ensure that a bang on the head does not become a life sentence to a progressive neurodegenerative disease. Dementia remains the world’s greatest unmet medical need. Research into tau-based therapeutics offers hope for all sports people currently afflicted or fearful of developing dementia from brain injuries or concussions.